Narendra Modi

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

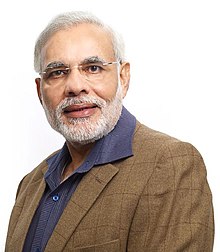

| Narendra Modi | |

|---|---|

| |

| 14th Chief Minister of Gujarat | |

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 7 October 2001 | |

| Governor | Sunder Singh Bhandari Kailashpati Mishra Balram Jakhar Nawal Kishore Sharma S. C. Jamir Kamla Beniwal |

| Preceded by | Keshubhai Patel |

| General Secretary of BJP | |

| In office 19 May 1998 – October 2001 | |

| Succeeded by | Sunil Shastri |

| National Secretary of BJP | |

| In office 20 November 1995 – 19 May 1998 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Narendra Damodardas Modi 17 September 1950 Vadnagar, Gujarat, India |

| Political party | Bharatiya Janata Party |

| Spouse(s) | Jashodaben (child marriage, estranged) |

| Alma mater | Gujarat University Delhi University |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Signature |  |

| Website | Official website |

Narendra Damodardas Modi ( pronunciation (help·info), born 17 September 1950) is an Indian politician and is the incumbent and 14th Chief Minister of the state of Gujarat. He is a member of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and is the prime ministerial candidate of the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance in the 2014 Indian general elections.

pronunciation (help·info), born 17 September 1950) is an Indian politician and is the incumbent and 14th Chief Minister of the state of Gujarat. He is a member of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and is the prime ministerial candidate of the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance in the 2014 Indian general elections.

Modi was a key strategist for the BJP in the successful 1995 and 1998 Gujarat state election campaigns, and was a major campaign figure in the 2009 general elections, eventually won by the Indian National Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA). He first became chief minister of Gujarat in October 2001 after the resignation of his predecessor, Keshubhai Patel, and following the defeat of BJP in the by-elections. In July 2007, he became the longest-serving Chief Minister in Gujarat's history, at which point he had been in power for 2,063 days continuously. He is currently serving his fourth consecutive term as Chief Minister.

Modi is a member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and is described as a Hindu nationalist by media, scholars and himself.[1][2][3][4] He is a controversial figure both within India and internationally[5][6][7][8] as his administration has been criticised for the incidents surrounding the 2002 Gujarat violence.[8][9] He has been praised for his economic policies, which are credited with creating an environment for a high rate of economic growth in Gujarat.[10] However, his administration has also been criticised for failing to make a significant positive impact upon the human development of the state.[11]

Contents

[hide]- 1 Early life and education

- 2 Early political career

- 3 Chief Minister of Gujarat

- 4 Central politics

- 5 International diplomacy

- 6 Personality and image

- 7 Awards and recognitions

- 8 References

- 9 External links

Early life and education

Modi was born on 17 September 1950 to a family of grocers in Vadnagar in Mehsana district of what was then Bombay Presidency (present-day Gujarat), India.[12] He was the third of six children born to Damodardas Mulchand Modi and his wife, Heeraben. He helped his father sell tea at Vadnagar railway station when a child and as a teenager he ran a tea stall with his brother near a bus terminus.[13][14] He completed his schooling in Vadnagar, where a teacher described him as being an average student, but a keen debater who had an interest in theatre.[13] That interest has influenced how he now projects himself in politics.[15]

Modi's parents arranged his marriage as a child, in keeping with the traditions of the Ghanchi caste. He was engaged at the age of 13 to Jashodaben Chimanlal and the couple were married by the time he was 18. They spent very little time together and were soon estranged because Modi decided to pursue an itinerant life.[13][16] However as per Modi's biographer Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, the marriage was never consummated.[17] Having remained silent on the question of marriage in four previous election campaigns, and having claimed that his status as a single person meant that he had no reason to be corrupt, Modi acknowledged Jashodaben as his legal spouse when filling in his nomination form for the 2014 Lok Sabha elections.[18][19]

Little is known of the two years that Modi spent travelling, probably in the Himalayas, and he resumed selling tea upon his return. He then worked in the staff canteen of Gujarat State Road Transport Corporation until he became a full–time pracharak (propagandist) of the RSS in 1970. He had been involved with the RSS as a volunteer from the age of eight and had come into contact with Vasant Gajendragadkar and Nathalal Jaghda, leaders of the Jan Sangh who later founded the BJP's Gujarat state unit.[13][20] After Modi had received some RSS training in Nagpur, which was a prerequisite for taking up an official position in the Sangh Parivar, he was given charge of Sangh's student wing, Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, in Gujarat. Modi organised agitations and covert distribution of Sangh's pamphlets during the Emergency.[13] Modi graduated in political science from Delhi University.[17] Modi remained a pracharak in the RSS while he completed his Master's degree in political science from Gujarat University.[21]

Early political career

Modi formally joined the RSS after the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971.[17] In 1975, the then Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency and jailed political opponents. Modi went underground in Gujarat, occasionally disguised, and printed and sent booklets against the central government to Delhi.[17] He also participated in the movement against the Emergency under Jayaprakash Narayan.[22][23] The RSS assigned Modi to the BJP in 1985.[20] While Shankarsingh Vaghela and Keshubhai Patel were the established names in the Gujarat BJP at that time, Modi rose to prominence after organising Murli Manohar Joshi's Kanyakumari-Srinagar Ekta yatra (Journey for Unity) in 1991.[13] In 1988, Modi was elected as organizing secretary of BJP's Gujarat unit,[24] marking his formal entry into mainstream politics.[17] As secretary, his electoral strategy was central to BJP's victory in the 1995 state elections.[20][25][26]

In November 1995, Modi was elected National Secretary of BJP.[27] In May 1998, Modi was elevated to the post of the General Secretary of the BJP and was transferred to New Delhi where he was assigned responsibility for the party's activities in Haryana and Himachal Pradesh.[25] After Vaghela, who had threatened to break away from BJP in 1995, defected from the BJP after he lost the 1996 Lok Sabha elections, Modi was promoted to the post of National Secretary of the BJP in 1998.[13] While selecting candidates for the 1998 state elections in Gujarat, Modi favored people who were loyal to Patel over those loyal to Vaghela, helping to put an end to the factional divisions within the party. His strategies were credited as being key to winning the 1998 elections.[25]

Chief Minister of Gujarat

Members of Modi's Council of Ministers with him at a Planning Commission meet in New Delhi

In 2001, Keshubhai Patel's health was failing, and the BJP had lost seats in the by-elections. Allegations of abuse of power, corruption and poor administration were being made, and Patel's standing had been damaged by his administration's handling of the Bhuj Earthquake of 2001.[25][28][29] As a result, the BJP's national leadership sought a new candidate for the office of chief minister, and Modi, who had aired his misgivings about Patel's administration, was chosen as a replacement.[13] L. K. Advani, a senior leader of the BJP, did not want to ostracise Patel and was worried about Modi's lack of experience in governance. Modi declined an offer to be Patel's deputy chief minister, informing Advani and Atal Bihari Vajpayee that he was "going to be fully responsible for Gujarat or not at all", and on 7 October 2001, Modi was appointed the Chief Minister of Gujarat, with the responsibility of preparing the BJP for elections in December 2002. As Chief Minister, Modi's ideas of governance revolved around privatisation and small government, which stood at odds with what Aditi Phadnis has described as the "anti-privatisation, anti-globalisation position" of the RSS.[28]

First term (2001-2002)

2002 Gujarat violence

Main article: 2002 Gujarat violence

On 27 February 2002, a train with several hundred passengers including large numbers of Hindu pilgrims was burned near Godhra, killing around 60 people.[a] Following rumors that the fire was carried out by Muslim arsonists, anti-Muslim violence spread throughout Gujarat.[32] Estimates of the death toll ranged from 900 to over 2,000, while several thousand more people were injured.[33][34] The Modi government imposed a curfew in major cities, issued shoot-at-sight orders, and called for the army to prevent the violence from escalating.[35][36] However, human rights organizations, opposition parties, and sections of the media all accused Gujarat's government of taking insufficient action against the violence, and even condoning it in some cases.[35][36][37] Modi's decision to move the corpses of the Kar Sevaks who had been burned to death in Godhra to Ahmedabad had been criticised for inflaming the violence.[38][39] In April 2009, the Supreme Court appointed a Special Investigation Team (SIT) to inquire into the Gujarat government and Narendra Modi's role in the incidents of communal violence.[37] The SIT reported to the court in December 2010 submitting that they did not find any substantial incriminating evidence against Modi of willfully allowing communal violence in the state.[40]

Despite the SIT report, Modi's involvement in the events of 2002 has continued to be debated. Though the SIT absolved Modi in April 2012 of any involvement in the Gulbarg Society massacre, one of the many riots that occurred in 2002,[41][42] the Supreme Court-appointed amicus curiae, Raju Ramachandran, observed on 7 May 2012 that Modi could be prosecuted for promoting enmity among different groups during the 2002 Gujarat violence. His main contention was that the evidence should be examined by a court of law because the SIT was required to investigate but not to judge.[43] His report was criticised by the SIT for relying heavily on the testimony of Sanjiv Bhatt, who they said had fabricated the documents used as evidence.[44] In July 2013, victim Zakia Jafri alleged that the SIT was suppressing evidence[45] however her plea against the clean-chit to Modi was rejected by the Courts. On 26 December 2013, an Ahmedabad court which was asked by the Supreme Court to handle the case, accepted the clean chit given to Modi in relation to the riots.[46]

In 2012, Maya Kodnani, another of Modi's former ministers from 2007 - 2009, was convicted of having participated in the Naroda Patiya massacre during the 2002 violence.[47][48] She was both the first female and the first MLA to be convicted in a post-Godhra riots case.[49] While initially announcing that it would seek the death penalty for Kodnani, Modi's government eventually pardoned her in 2013 and settled for a prison sentence.[50][51][52]

2002 election

Main article: Gujarat legislative assembly election, 2002

In the aftermath of the violence, there were widespread calls for Modi to resign from his position as chief minister of Gujarat. These came from both within and outside the state, including including from the leaders of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam and the Telugu Desam Party, which were allies in then BJP-led NDA government at the centre. The opposition parties stalled the national parliament over the issue.[53][54] In April 2002, at the national executive meeting of BJP at Goa, Modi submitted his resignation; however, it was rejected by the party.[55] On 19 July 2002, Modi's cabinet had an emergency meeting and offered its resignation to the Governor of Gujarat, S. S. Bhandari, and the assembly was dissolved.[56][57] In the subsequent elections, the BJP, led by Modi, won 127 seats in the 182-member assembly.[58] Anti-Muslim rhetoric formed a significant part of Modi' campaign for the election.[59]

Second term (2002–2007)

Despite using anti-Muslim rhetoric during the campaign,[59][60][61] Modi's emphasis shifted during his second term from Hindutva to the economic development of Gujarat.[28] Modi's decisions curtailed the influence of organizations of the Sangh Parivar such as the Bharatiya Kisan Sangh (BKS) and the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP),[62] which had become entrenched in Gujarat after the decline of Ahmedabad's textile industry.[28] Modi dropped Gordhan Zadafia, an ally of his former Sangh co–worker and VHP state chief Praveen Togadia, from the cabinet ministry. When the BKS launched a farmers' agitation, Modi ordered their eviction from houses provided by the state government. Modi's decision to demolish 200 illegal temples in Gandhinagar deepened the rift with VHP.[62][63] Various organisations of the Sangh were no longer consulted nor informed of Modi's administrative decisions prior to their enactment.[62]

The changes brought by Modi in the period 2002–2007 has led to Gujarat being called an attractive investment destination. Aditi Phadnis, author of Political Profiles of Cabals & Kings and columnist in the Business Standard, writes that "there was sufficient anecdotal evidence pointing to the fact that corruption had gone down significantly in the state... if there was to be any corruption, Modi had to know about it".[28] Modi started financial and technology parks in the state. During the 2007 Vibrant Gujarat summit, real estate investment deals worth  6.6 trillion were signed in Gujarat.[28]

6.6 trillion were signed in Gujarat.[28]

Despite his focus on economic issues during the second term, Modi continued to be criticised for his relationship with Muslims. Atal Bihari Vajpayee, then Prime Minister of India, who had asked Modi not to discriminate between citizens in the aftermath of the 2002 Gujarat violence and had pushed for his resignation as Chief Minister of Gujarat,[64][65] distanced himself from Modi and reached out to North Indian Muslims before the 2004 elections to the Lok Sabha. After the elections, Vajpayee held that the violence in Gujarat had been one of the reasons for BJP's electoral defeat and acknowledged that not removing Modi immediately after the Gujarat violence was a mistake.[66][67]

Terrorism and elections in 2007–2008

Further information: Gujarat legislative assembly election, 2007

In the run up to the assembly elections in 2007 and the general election in 2009, the BJP stepped up its rhetoric on terrorism.[68] On 18 July 2006, Modi criticised the Indian Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, "... for his reluctance to revive anti-terror legislations" such as the Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act. He asked the national government to allow states to invoke tougher laws in the wake of the 2006 blasts in Mumbai.[69] Around this time Modi frequently demanded the execution of Afzal Guru,[70] a collaborator of the Pakistani jihadists who had been convicted of terrorism for his involvement in the 2001 Indian Parliament attack.[71][b] As a consequence of the November 2008 Mumbai attacks, Modi held a meeting to discuss security of Gujarat's 1,600 km (990 mi) long coastline which resulted in the central government authorisation of 30 high–speed surveillance boats.[72]

In July 2007, Modi completed 2,063 consecutive days as chief minister of Gujarat, making him the longest-serving holder of that post.[73] The BJP won 122 of the 182 seats in the state assembly in the 2007 election, and Modi continued as chief minister.[74]

Third term (2007–2012)

Development projects

The Sardar Sarovar Dam, undergoing a height increase in 2006.

Modi's Government has focused on clean energy sources for meeting the energy requirements of the state, such as hydroelectric power (pictured above) and solar energy in addition to biofuels and wind energy.[75]

Successive BJP governments under Patel and Modi supported NGOs and communities in the creation of infrastructure projects for conservation of groundwater. Gujarat is a semi-arid state and, according to Tushaar Shah, was "... never known for agrarian dynamism". By December 2008, 500,000 structures had been constructed, of which 113,738 were check dams. While most check dams remained empty during the pre-monsoon season, they helped recharge the aquifers that lie beneath them.[76] 60 of the 112 tehsils which were found to have over–exploited the groundwater table in 2004 had regained their normal groundwater level by 2010,[77] meaning that Gujarat had managed to increase its groundwater levels at a time when they were falling in all other Indian states. As a result, production of genetically-modified Bt cotton, which could now be irrigated using tube wells, increased to become the largest in India.[76] The boom in cotton production and utilization of semi–arid land[78] saw the agriculture growth rate of Gujarat increase to 9.6% in the period 2001–2007.[79] Though public irrigation measures in the central and southern areas, such as the Sardar Sarovar Project, have not been as successful in achieving their aims,[76] for the decade 2001–2010, Gujarat recorded an agricultural growth rate of 10.97%, the highest among all Indian states.[78]

The system of supplying power to rural areas has been changed radically and has had a greater impact on agriculture than the irrigation works. While states such as Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu provided free electricity to farms, and most other states provided subsidised power, the Gujarat government between 2003–2006 reacted to concerns that such measures result in waste of power and groundwater. With the Jyotigram Yojana scheme, based on ideas developed by the International Water Management Institute, the agricultural electricy supply was rewired to separate it from other rural power supplies. Then, the electricity used by farms was rationed to fit scheduled demand for irrigation, which consequently reduced the cost of the subsidy. At first, the farmers objected to this, but came to realise that the supply suffered less from interruption, was more consistent in voltage and was available when they most needed it for irrigation purposes. Other states have since begun to adopt similar, although not identical, strategies.[76]

Debate on Gujarat's development under Modi

Narendra Modi addressing law graduates at the Gujarat National Law University.

Modi's government has worked to brand Gujarat as a state of dynamic development, economic growth and prosperity, using the slogan "Vibrant Gujarat".[80][81][82] However, critics have pointed to Gujarat's relatively poor record on human development, poverty alleviation, nutrition, and education. The state is 13th in India for poverty, 21st for education, 44.7 percent of children under five are underweight and 23 percent are undernourished putting the state in the "alarming" category on the India State Hunger Index.[83] In contrast, officials from the state of Gujarat claim that Gujarat outperformed India as a whole in the rates of improvement of multiple human indicators, such as female education, between 2001 and 2011. Furthermore, they claim that the school dropout rates declined from 20 percent in 2001 to 2 percent in 2011, and that maternal mortality declined by 32 percent from 2001 to 2011.[84]

Political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot asserts that the development in Gujarat has been limited to the urban middle class, while rural dwellers and lower castes have become increasingly marginalised. He cites the fact that Gujarat ranks 10th among the 21 Indian states in the Human Development Index, which he attributes to the lower development in rural Gujarat. He states that under Modi, the number of families living below the poverty line has increased, and that particularly rural adivasi and dalits have become increasingly marginalised.[85] In July 2013, Economics Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen criticised Narendra Modi's governance record and said he did not approve of it, saying that under Modi's administration, Gujarat's "record in education and healthcare is pretty bad".[86] However, economists Arvind Panagariya and Jagdish Bhagwati state that Gujarat's social indicator improved from a much lower baseline than other Indian states. They claim that Gujarat's performance in raising literacy rates has been superior to other states in India, and the "rapid" improvement of health indicators in Gujarat as evidence that "its progress has not been poor by any means."[87]

Election Commission's cautioning

In 2007, Modi was cautioned by the Election Commission of India for his speech at Mangrol, in which he justified the extrajudicial killing of Sohrabuddin Sheikh. The Commission considered the speech to be "indulging in an activity that might aggravate existing differences between different communities."[88] Modi had made this speech in response to Sonia Gandhi's speech calling him a "merchant of death", referring to Sohrabuddin's killing.[89] Amit Shah, a close aid of Modi's, was indicted for being involved in the killing.[90]

Sadbhavana Mission and fasts

During late 2011 and early 2012, Modi undertook a series of fasts as part of a Sadbhavna Mission (Goodwill Mission), meant to reach out to the Muslim community in Gujarat.[91] Modi announced that he believed that his fast would "further strengthen Gujarat’s environment of peace, unity and harmony."[92]

The mission started on 17 September 2011 in Ahmedabad with a three-day fast. He subsequently observed 36 fasts in 26 districts and eight cities.[93] However, these fasts were not well received by all Muslims; for example, one incident in which Modi refused to wear a skull cap offered to him by a Muslim cleric named Sayed Imam Shahi Saiyed[94] of a Dargah in Piranawas deemed an insult by the cleric.[95] Another example occurred when Modi was fasting in Godhra, the site of the train burning that sparked the 2002 riots: a number of activists were detained for allegedly planning rallies against Modi.[96][97] Although some criticised his fast as a public relations mission,[98] Modi himself denied that the mission was about wooing "any particular community or religion".[99]

In 2011, the Supreme Court complimented the Gujarat Government for its land acquisition policy as there were "no complaints of any forcible acquisition" whereas issues of farmers and poor being uprooted are pouring in from all other states.[100]

Appointments and disagreements with the governor

On 25 August 2011, the governor of Gujarat, Kamla Beniwal, appointed Justice R. A. Mehta to the post of Lokayukta of Gujarat, a critical anti–corruption post that had been lying vacant since 2003. Mehta was recommended for the post by the Chief Justice of the Gujarat High Court in June 2011.[101] Beniwal made this decision without consulting Modi and his council of ministers.[102] This marked the beginning of a strained relationship between Modi and Beniwal. On 25 September 2011, Modi accused the Governor of running a parallel government in the state supported by the Indian National Congress party and demanded that she be recalled.[103] The appointment of Mehta was challenged in the High Court by the Gujarat government. The two-member high court bench gave a split verdict on 10 October 2011. A third member upheld the appointment in January 2012.[104]

Modi has also accused Beniwal of delaying a bill for reservation of 50% of seats in local government for women.[105]

Press and public relations

In 2011, the Gujarat state organisation of the Indian National Congress party banned the Gujarati-language TV 9 television channel from covering its events and prevented access to its press conferences.[106] Modi criticised this decision, saying that

Journalists on Twitter who spoke against Congress, were blocked. Here they banned a TV channel. Their crime is that they exposed cracks in the ghar nu ghar (own your home) scheme of the Congress. Yet this party talks about democracy.[107]

Modi interacted with netizens on Google+ on 31 August 2012.[108] The chat session was also broadcast live on YouTube.[108] The questions were submitted before the chat, and those broadcast were mostly based on issues about education, youth empowerment, rural development and causes of urbanisation.[109] The hashtag #ModiHangout became the most trending term in India at Twitter on the day of the session, whereas #VoteOutModi, used by Modi's opponents, became the third most trending term in the country.[108] The event made Modi the first Indian politician to interact with netizens through live chat on the internet.[110]

Fourth term (2012–present)

Further information: Gujarat legislative assembly election, 2012

In the 2012 Gujarat legislative assembly elections, Modi won from the constituency of Maninagar with a majority of 86,373 votes over Sanjiv Bhatt's wife, Shweta, who was contesting for the Indian National Congress.[112] The BJP won 115 of the 182 seats, continuing the majority that the party has had throughout Modi's tenure,[113] and allowing the party to form the government, as it has in Gujarat since 1995[114]

In later by-elections, the BJP won an additional four assembly seats and 2 Lok Sabha seats that were all held by the Indian National Congress prior to the by-elections, even though Modi never campaigned for its candidates.[115] This brought the number of seats held by the BJP in the state assembly up to 119.

Central politics

Path to candidacy for prime minister

Modi had been a significant figure in the 2009 national general election campaign.[116][117] In March 2013, Modi was appointed to the BJP Parliamentary Board, the party's highest decision-making body, and was chosen to be chairman of the party's Central Election Campaign Committee.[118][119] On 10 June 2012, Modi was selected to head the poll campaign for 2014 general election, at the national level executive meeting of BJP. The party's senior leader and founding member Lal Krishna Advani resigned from all his posts at the party following the selection, protesting against leaders who were "concerned with their personal agendas"; the resignation was described by The Times of India as "a protest against Narendra Modi's elevation as the chairman of the party's election committee". However, Advani withdrew his resignation the next day at the urging of RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat.[120] In September 2013, BJP announced Modi as their prime ministerial candidate for the 2014 Lok Sabha election.[121]

2014 general election

Main article: Indian general election, 2014

Narendra Modi is contesting the election from two constituencies: Varanasi[122] and the Vadodara.[123] His candidacy is supported by spiritual leaders Ramdev and Morari Bapu,[124] and by economists Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya, who have stated that they, "...are impressed by Modi's economics." [125] His detractors include Nobel Prize laureate economist Amartya Sen, who said that he did not want Modi as a Prime Minister because he had not done enough to make minorities feel safe, and that under Modi, Gujarat's record in health and education provision has been "pretty bad".[86]